When LLMs Review Cryptography Papers

This post is cross-posted to the zkSecurity blog.

Google Research recently published a collection of case studies on Accelerating scientific research with Gemini. The 150-page document explores a variety of techniques, including using the LLM as an adversarial reviewer.

To my surprise, the case study for this specific technique was about cryptography. And not any kind of cryptography, this was about SNARGs! Since this hits so close to home, here’s my quick summary of what happened and how LLMs found a bug in a cryptography paper that humans missed.

Context: paper and timeline

The paper we are looking at is written by Ziyi Guan and Eylon Yogev, and was originally titled SNARGs for NP from LWE. Let me quickly unpack this title:

- a SNARG (succinct non-interactive argument) is pretty much the same thing as a SNARK (succinct non-interactive argument of knowledge) but with slightly weaker security properties. They are easier to construct than SNARKs, which makes them a useful stepping stone in our research on constructing SNARKs.

- NP is how complexity theorists talk about “computation that can be run on real-world hardware”.

- LWE stands for learning with errors. It is one of the fundamental assumptions we use to construct lattice-based cryptography and is considered to be resistant to quantum computers. Importantly, it is a falsifiable assumption1.

SNARGs for NP from LWE is a significant result! So far, we only know how to make SNARGs for NP in idealized models (like the random oracle model in hash-based proofs), using non-falsifiable assumptions (like the knowledge of exponent assumption in Groth16) or using very-powerful-but-impossible-to-implement cryptography (like indistinguishability obfuscation). The result was published on ePrint, announced on X and celebrated by the community.

Unfortunately, the party was short-lived. A few days later, Ziyi announced on X that a bug was found in the paper, and that she and Eylon did not know how to fix it. They eventually updated the paper, removing the claim of constructing SNARGs for NP from LWE but salvaging other aspects of their result.

This is where I thought the story ended. That was, until I randomly stumbled on the Google Research document and saw that Ziyi and Eylon are co-authors. As it turns out, the bug was found using Gemini and the discovery is recorded in Section 3.2 of Google Research’s document.

LLM prompting strategy

While I won’t be covering what the bug is in this post, I do want to take a look at how the bug was found and how the LLM was guided to do so. The global strategy is what has been previously labelled LLM-as-a-Judge. However, as you might expect, the prompt was more elaborate that simply asking the LLM “check that this paper is correct”.

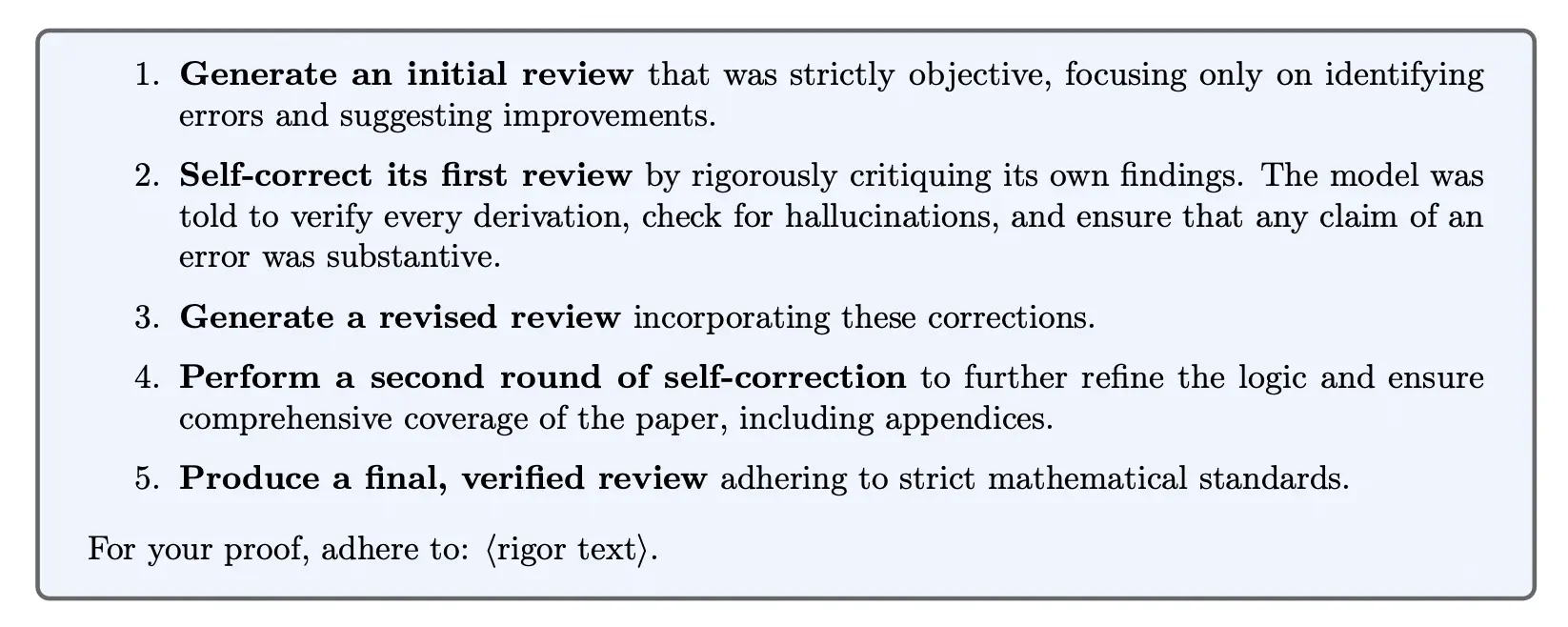

Instead, the authors implemented what they call a “rigorous iterative self-correction prompt”. Essentially, this is two iterations of a loop asking the model to review the paper, and review its review. The figure below is lifted from the Google Research paper and details the prompting strategy:

Iterative self-correction prompt. Figure taken from the Google Research paper.

Unfortunately, the specific model and “rigor text” used are not publicly available. It is also interesting to note that the report indicates that the LLM produced “noise”, in other words that it also flagged less relevant issues. However, it does not clearly indicate whether the LLM’s output also included false positives.

LLMs in academic research

Recently, my colleague Yoichi used LLMs to formalize one of my recent papers in Lean. The success of this outcome highlights a very exciting direction for academic research: as long as we can express our ideas and proofs clearly on paper, we can use LLMs to cross the final mile and write formally verified proofs.

The flipside of this is that conferences will soon be swamped with AI-assisted submissions and probably will not have the time to verify all the incoming work. The example from Google Research’s report gives us one potential solution in using LLMs for review.

While I’m glad that this specific case study worked nicely (and focuses on a topic I’m interested in!), I am curious to see how this generalizes. Does the technique work reliably on a large sample of papers? What is the false-positive rate? Regardless, these are very exciting times to be playing with these tools and I am glad that big teams share their findings in such comprehensive reports.

LLMs in audits

It is worth noting that we, at ZKSecurity, have also been using these methods in our audits. Our recently-released tool, zkao, automates a lot of this work. A first pass of agents review the codebase and report on their findings. We then get a second wave of agents to review the findings. This feedback loop can be run multiple times by defining zkao workflows. The tool can do a lot more and I encourage you to read more about it and sign up for early access.

In our testing, we have noticed that LLM-as-a-Judge is more effective when the reviewing pass is done by a different personality/agent. Likewise, using different models to review each other’s work seems to be more effective. Why this happens or whether it happens at all is still unknown and remains fertile ground for experimentation.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to David for reviewing this article and sharing additional insights on using LLM-as-a-Judge in zkao.

-

oversimplifying, we say that an assumption is falsifiable if it can be shown to be false using computational methods (e.g., constructing an efficient algorithm that solves a problem). In contrast, a non-falsifiable assumption cannot be tested in this way. We much prefer using a falsifiable assumption since we can get a sense of “how true it is” based on the fact that no-one has broken it so far. ↩︎